James Baldwin didn’t write about sex work to shock. He wrote about it because it was real - because the bodies of Black women and queer men were constantly traded, exploited, and erased in plain sight. In novels like Go Tell It on the Mountain, Giovanni’s Room, and Another Country, prostitution isn’t a subplot. It’s a structural truth. A way for people without power to survive in a world that refuses them dignity. When Baldwin describes a woman trading her body for rent, or a man selling intimacy to avoid homelessness, he’s not painting a scene of moral decay. He’s mapping the cost of racism, homophobia, and poverty on the human skin.

There’s a strange echo in today’s conversations about adult services - like happy ending massage - where the line between transaction and tenderness gets blurred. People seek connection, relief, escape. Baldwin understood that. He didn’t romanticize it. He showed how desperation and desire live in the same breath. In 1950s Paris, where he lived for years, Black American men and women often turned to sex work not because they wanted to, but because no other door opened. The same logic applies now, in places like Dubai, where economic displacement pushes people into informal economies - whether it’s a massage parlour labeled as "spa" or a street corner in Harlem.

The Body as a Site of Resistance

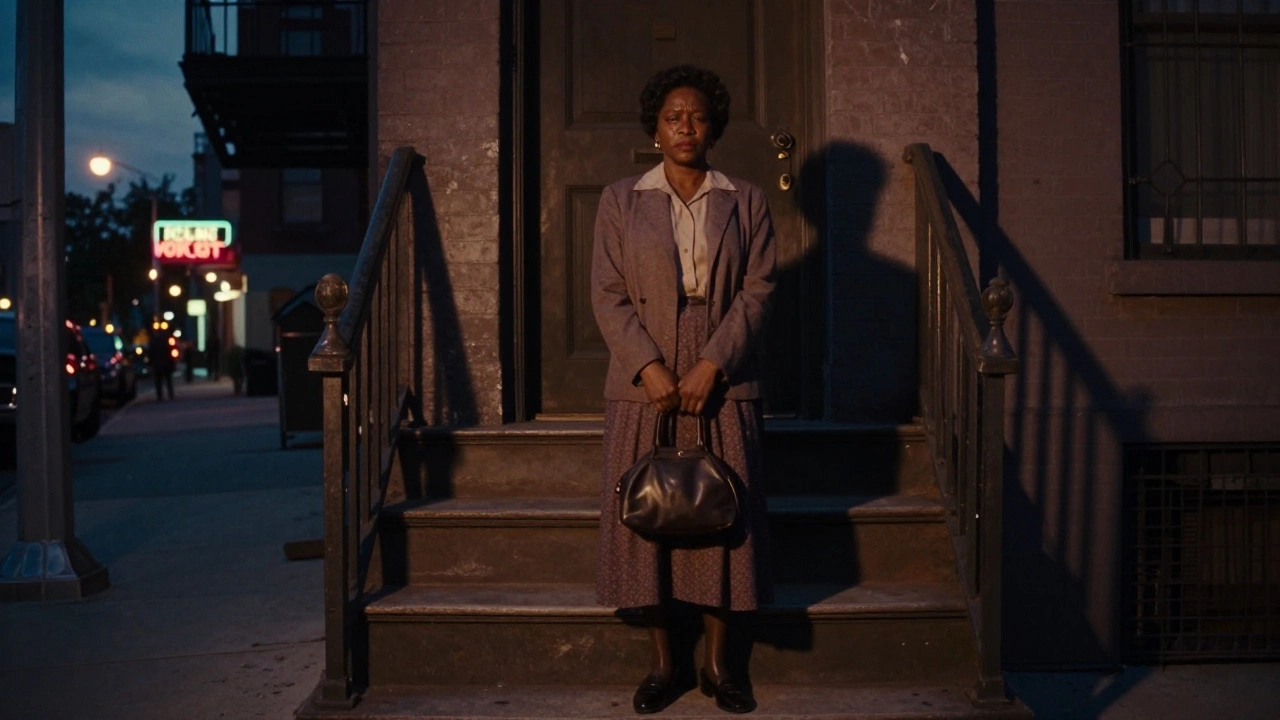

Baldwin’s characters don’t just endure sex work - they use it to claim agency. In Another Country, Ida’s past as a sex worker isn’t hidden. It’s central to her voice. She doesn’t apologize for it. She turns her experience into armor. When white characters try to pity her, she laughs. "You think I’m broken?" she says. "I’m the only one here who knows how to survive."

That’s not the kind of story you see in mainstream portrayals. Most films and TV shows reduce sex workers to victims or villains. Baldwin gave them language. He let them speak. He showed how their bodies became the only currency they could control. In a society that denied them education, jobs, and safety, sex work wasn’t failure - it was adaptation.

Today, you can find similar dynamics in global cities. In Dubai, for example, the underground economy thrives under the guise of wellness. russian massage dubai is a phrase that pops up in search results - not because Russians run most spas, but because the label implies discretion, intimacy, and a service that doesn’t ask questions. Baldwin would recognize the code. He knew how language hides what’s uncomfortable. "Massage" can mean relief. Or it can mean transaction. The word doesn’t change. The power does.

Queer Desire and the Cost of Visibility

It’s easy to forget that Baldwin was writing about queer Black men when being openly gay could mean jail, violence, or exile. In Giovanni’s Room, David’s relationship with Giovanni ends in tragedy - not because love failed, but because the world wouldn’t allow it to exist without punishment. Giovanni, a poor Italian immigrant, works as a bartender and later as a sex worker to survive. His body is the only asset he has. When he turns to clients, it’s not for pleasure. It’s to pay for a room, for food, for time.

Baldwin didn’t frame this as a moral failing. He framed it as a consequence. A system that denies queer people jobs, family support, and legal protection forces them into survival economies. Today, queer youth in the U.S. are still overrepresented in homeless populations. Many turn to survival sex work - not because they choose it, but because the alternatives are worse. Baldwin saw this in the 1950s. Nothing’s changed, just the language.

There’s a modern version of this in places like Dubai, where the demand for private, anonymous services has grown. massage republic dubai isn’t just a business name. It’s a signal. A promise of privacy. Of silence. Of not being judged. Baldwin’s characters would understand that. They lived in a world where being seen meant being hunted. Today, the hunt is quieter. But it’s still there.

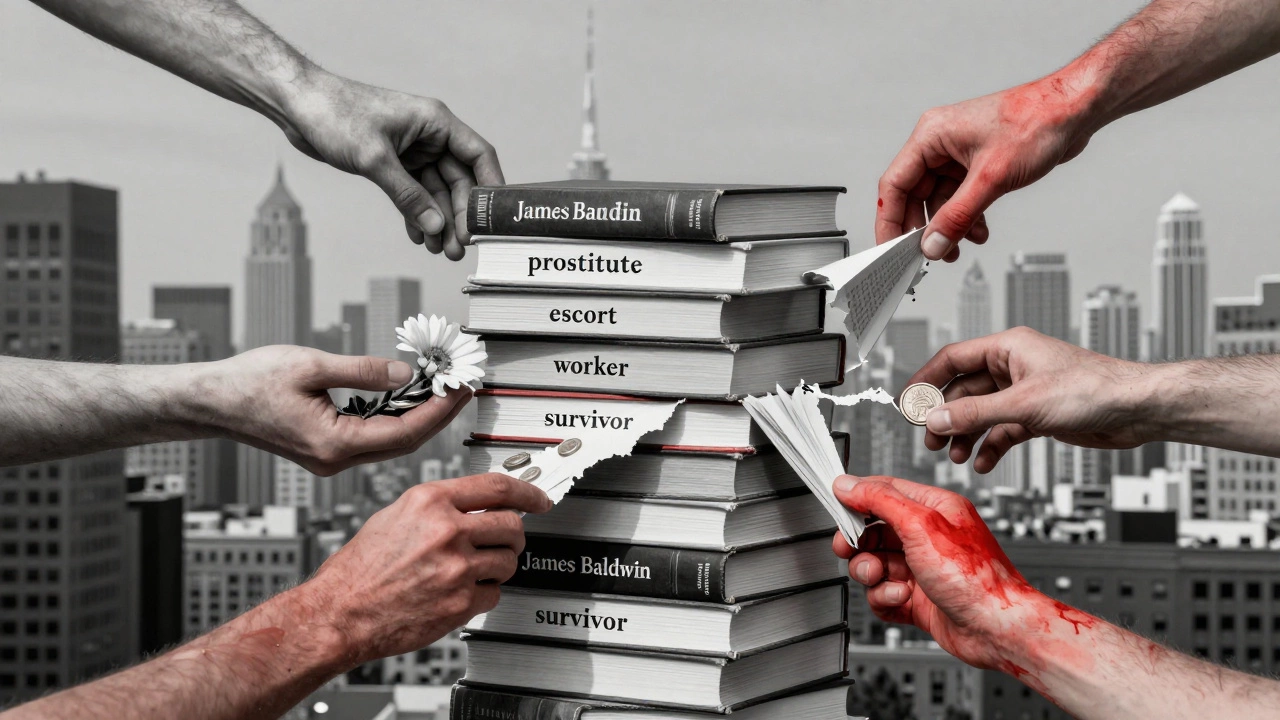

Language as a Weapon and a Shield

Baldwin was a master of words. He knew how language could lift someone up - or bury them. The word "prostitute" was used to dehumanize. "Escort" was used to sanitize. "Worker" was rarely used at all. He gave his characters the right to define themselves. Ida doesn’t call herself a prostitute. She calls herself a woman who did what she had to do.

That’s the same tension we see today. Online platforms use terms like "companionship," "entertainment," or "therapy" to mask what’s really happening. The industry hides behind euphemisms. So do the people who use it. In Baldwin’s time, people whispered. Now, they Google. russian massage dubai is a search term. It’s not about geography. It’s about anonymity. It’s about not being labeled.

Baldwin wrote about the silence between words. The unsaid. The shame. The unspoken fear that if you admit what you do to survive, you’ll lose everything - your family, your job, your name. That’s still true. The tools have changed. The stakes haven’t.

Why This Still Matters

James Baldwin didn’t write to be read by academics. He wrote to be read by people who felt invisible. By the ones who scrubbed floors after long nights. By the ones who kissed strangers for cash. By the ones who were told they were broken, but knew they were just surviving.

His work isn’t history. It’s a mirror. Today, in cities from New York to Dubai, people still trade intimacy for survival. The difference is, now they do it on apps. They use coded language. They hide behind reviews. They pay for happy ending massage not because they’re seeking pleasure, but because they’re seeking a moment of peace - a few minutes where they aren’t judged, aren’t asked for papers, aren’t reminded they’re less than.

Baldwin knew that. He wrote about it because he lived it. He didn’t need statistics. He had his own body. His own scars. His own truth.

If you want to understand sex work in modern America - or anywhere - read Baldwin. Not because he gives you answers. But because he asks the right questions. Why do people sell their bodies? Who made it the only option? And who gets to decide what’s moral - and who pays the price?